This is part 6 of a multipart series.

In an earlier post, I wrote about some of the more general, introductory texts on Daoism that I had read in my youth. As I continued my studies into Daoism, my reading progressed into more specific areas, including Traditional Chinese Medicine, Taiji and Qigong, Yi Jing (commonly written as I Ching), and The Art of War.

You might think that war would be a strange area of study for a Daoist. Wouldn’t Daoists be more interested in the way of peace? And you would be right. In chapter 8 of the Dao De Jing, (Gia-Fu / English translation throughout), Laozi says, “In dealing with others, be gentle and kind,” and, “No fight: No blame.” But the fact is that Daoist scholars commonly had roles in the courts, as advisors to Lords, Dukes, and Emperors. Of course, these rulers would busy themselves in the business of war, and their Daoist advisors would try to channel the rulers into less destructive paths.

Many passages in the Dao De Jing are instructions for how to advise Lords, in both military and non-military matters. Chapter 60 says, “Ruling the country is like cooking a small fish,” an aphorism that could be repeated by the Daoist to their advisee to impart the idea that ruling needs to be done with a gentle hand, and forceful or blatant tactics are bound to be ruinous.

Chapter 30 provides an example of specific advice for rulers in the conduct of war:

Whenever you advise a ruler in the way of Tao,

Counsel him not to use force to conquer the universe.

For this would only cause resistance.

Thorn bushes spring up wherever the army has passed.

Lean years follow in the wake of a great war.

Just do what needs to be done.

Never take advantage of power.

Achieve results,

But never glory in them.

Achieve results,

But never boast.

Achieve results,

But never be proud.

Achieve results,

Because this is the natural way.

Achieve results,

But not through violence.

Many other passages in the Dao De Jing provide commentary on the conduct of war, such as chapter 57, which states, “The sharper men’s weapons, / The more trouble in the land.” And from chapter 31:

When many people are being killed,

They should be mourned in heartfelt sorrow.

That is why a victory must be observed like a funeral.

Before moving on, it’s worth noting that not all Daoists found the practice of advising Dukes and Lords commendable. Zhuang Zhou, (commonly written Chuang Tzu) advised his fellow Daoists great caution towards such activity in his chapter on The World of Men. For example (Burton Watson translation):

You had best keep your advice to yourself! Kings and dukes always lord it over others and fight to win the argument. You will find your eyes growing dazed, your color changing, your mouth working to invent excuses, your attitude becoming more and more humble, until in your mind you end by supporting him. This is to pile fire on fire, to add water to water, and is called ‘increasing the excessive.’

The first time I read The Art of War, I read the Thomas Cleary translation. Cleary made invaluable contributions to the study of Daoism by translating many works into English that have never otherwise been translated, as well as providing modern, accurate translations for many works whose existing translations left something to be desired. I find his renditions to be sometimes a little stiff or clinical, but they are clearly semantically accurate and historically informed. Semantically accurate, that is, as far as it is possible to translate these writings into English. The Chinese language, and Chinese patterns of thought, are distinctly different to western languages and patterns of thoughts, and sometimes a direct rendering is simply impossible. The content of the The Art of War is largely both mundane and clear-cut, so it shouldn’t be as much of a problem for this text. But I seem to remember being quite unsatisfied with the translation when I read it back in the 90s.

I only find one copy of The Art of War on my shelves today, translated by Lionel Giles, one of the earliest translators of Chinese philosophical texts. The translation is satisfactory, and the book contains a great deal of valuable-looking commentary and notes. I also found multiple free PDFs online of his rendition without the commentary. (It seems to have fallen out of copyright.) I’ll be using the Giles in the quotes in this article.

Dating to about the 5th century BC, and attributed to the military strategist Sunzi, The Art of War is commonly billed as the first ever book on military strategy. It is filled with all kinds of practical advice at the strategic and operational levels for carrying out wars. Most of it is still relevant today. There’s so much good stuff in this book! It’s hard to pick only a few examples. Here are a few pieces of advice for operations from chapter 9: The Army on the March:

After crossing a river, you should get far away from it. When an invading force crosses a river in its onward march, do not advance to meet it in mid-stream. It will be best to let half the army get across, and then deliver your attack. [verses 3-4]

All armies prefer high ground to low, and sunny places to dark. [verse 11]

If you are careful of your men, and camp on hard ground, the army will be free from disease of every kind, and this will spell victory. [verse 12]

Here’s some particularly insightful advice regarding supply lines from chapter 2: Waging War:

Hence a wise general makes a point of foraging on the enemy. One cartload of the enemy's provisions is equivalent to twenty of one's own, and likewise a single picul of his provender is equivalent to twenty from one's own store. [verse 15]

The book speaks a great deal about concealing your plans from your enemy, and discerning their true intentions. This one feels particularly insightful:

When envoys are sent with compliments in their mouths, it is a sign that the enemy wishes for a truce. [chapter 9, verse 38]

It also speaks a great deal on the dangers of over-committing, both in terms of military assets and national resources. Both the USSR and the USA would have done well to heed Sunzi in regards to Afghanistan, when he says:

In war, then, let your great object be victory, not lengthy campaigns. [chapter 2, verse 19]

While not strictly a Daoist text, The Art of War is strongly influenced by Daoist philosophy. An unmistakable sign of Daoist influence can be found in this water analogy found in chapter 6: Weak Points and Strong:

Military tactics are like unto water; for water in its natural course runs away from high places and hastens downwards. So in war, the way is to avoid what is strong and to strike at what is weak. Water shapes its course according to the nature of the ground over which it flows; the soldier works out his victory in relation to the foe whom he is facing. Therefore, just as water retains no constant shape, so in warfare there are no constant conditions. [chapter 6, verses 29-32]

Water is a very common metaphor for the Daoists, used to portray aspects of wu wei, or “actionless action”. Compare this passage from chapter 78 of the Dao De Jing:

Under heaven nothing is more soft and yielding than water.

Yet for attacking the solid and strong, nothing is better;

It has no equal.

The weak can overcome the strong;

The supple can overcome the stiff.

Under heaven everyone know this,

Yet no one puts it into practice.

I’ve heard it said that the lords who wished to do well in war were enticed by the strategic content of the book into engaging the Daoist perspective presented in select verses. But advising a lord in the strategies of war, or even carrying out the war yourself, and following the Dao, are one and the same path. If war is going to happen in any event, we might as well do it well. And the best way to fight a war is to do as little as possible. In chapter 3: Attack by Stratagem, Sunzi says:

In the practical art of war, the best thing of all is to take the enemy's country whole and intact; to shatter and destroy it is not so good. So, too, it is better to recapture an army entire than to destroy it, to capture a regiment, a detachment or a company entire than to destroy them. Hence to fight and conquer in all your battles is not supreme excellence; supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy's resistance without fighting. Thus the highest form of generalship is to balk the enemy's plans; the next best is to prevent the junction of the enemy's forces; the next in order is to attack the enemy's army in the field; and the worst policy of all is to besiege walled cities. [chapter 3, verses 1-3]

Therefore the skillful leader subdues the enemy's troops without any fighting; he captures their cities without laying siege to them; he overthrows their kingdom without lengthy operations in the field. [chapter 3, verse 6]

While not explicitly a Daoist text, The Art of War is an extremely valuable text for Daoists to study. Daoists know that on the path to enlightenment, all seven or eight of their energy bodies need to be cleared, starting with the physical body. They are on a long-term campaign with many potential impasses, pitfalls, and bottlenecks. How to approach and engage the process requires deep strategy. While it addresses a separate area of concern, The Art of War shows the Daoist practitioner how to formulate a successful strategic approach.

I’ve gone on for over 1500 words already, but I really wanted to talk about some other books as well! When you go around talking about The Art of War, someone is bound to ask if you’ve read The Book of Five Rings, by Miyamoto Musashi. So I did so, and I really didn’t like it. The advice provided seemed pretty plain and uninteresting compared to the teachings found in The Art of War. And each short section ended with some words of negative sentiment expressing the importance of studying his work. Here are two examples from a free PDF I found online:

Besides, some men have not the strength of others. In my doctrine, I dislike preconceived, narrow spirit. You must study this well.

Without the correct principle the fight cannot be won. The spirit of my school is to win through the wisdom of strategy, paying no attention to trifles. Study this well.

For whatever reason, I found these chastisements quite annoying. I was pretty head-strong at the time. I should probably give this book another try. Musashi was an extremely skilled swordsman who lived in Japan in the 16th and 17th centuries. He retired to a cave at the end of his life to live as a hermit and write this book. The story of his life was fictionalized into a novel called Musashi, by Eiji Yoshikawa. This is an absolutely delightful story that demonstrates a wide range of Zen and Daoist principles. It’s well worth the read.

I must also mention the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, by Luo Guanzhong, when discussing the art of war. This novel recounts a period of war between many smaller states in China in the 3rd century AD, between the Han and Jin dynasties. The story mainly follows the efforts of Liu Bei – a distant relative to the Han imperial family – to become emperor in these chaotic times. Liu gathered many great people around him to help him in his cause, including Guan Yu, a legendary warrior who was later deified, and Zhuge Liang, a master strategist.

The story and the characters in this romance are quite compelling, but the true draw of this novel is in the countless demonstrations of practical principles of the art of war. Because these are not discussed in the abstract, but in terms of actual people in real situations, the psychology of the people involved comes into full play. Zhuge Liang comes off as particularly brilliant in this story, and quickly became an absolute favorite of mine.

I must confess, I have not actually read this novel yet. Instead, I watched a wonderful 60+ hour TV series based on the novel. The English subtitles were barely translated. They were obviously the work of a native Chinese speaker who hardly knew English. I found this to be the best possible translation, because all the original intent and meaning of the Chinese words were front and center, however embarrassingly broken the English text. So much meaning can get lost between Chinese and English, and sometimes, doing the least possible is best.

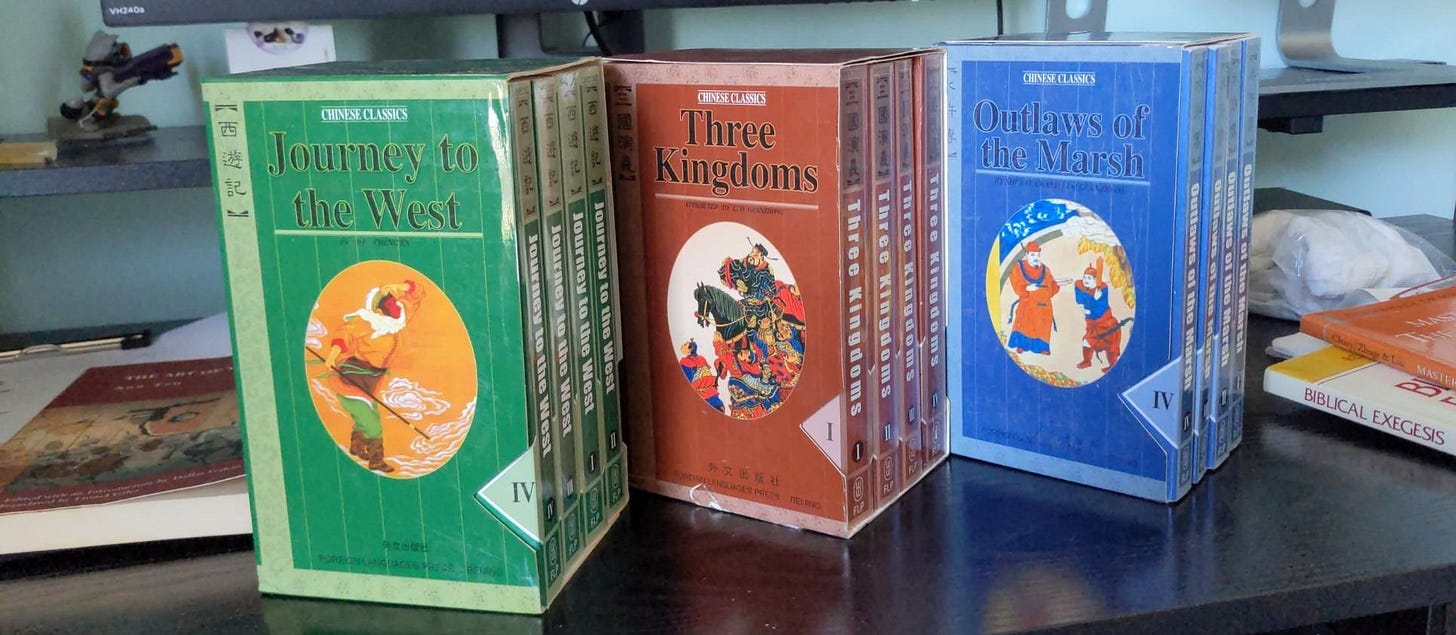

I do intend to read this book at some point. I have a copy of it, along with two other of the four great classic Chinese novels, in multi-volume paperback sets. I’ve read the Outlaws of the Marsh, and I’m about a third of the way through Journey to the West. These are both great stories as well, although they are both quite repetitive.

More recently, I read Mastering the Art of War, half of which consists of essays on strategy by Zhuge Liang. The second half is a work by Liu Ji, a master strategist from the 14th century who helped Zhu Yuanshang defeat the Mongol occupation and establish the Ming dynasty. Thomas Clearly, the translator, claimed to have collated Zhuge Liang’s essays from a collection of works by and about Zhuge Liang entitled Records of the Loyal Lord of Warriors. I am unable to find any reference to this collection of works. Having no other English translations, these essays are only accessible to English speaking student thanks to the skill and efforts of Cleary. Too bad he is no longer with us, as he was our best chance at getting a complete translation of this Records of the Loyal Lord of Warriors. I found Zhuge’s essays to be insightful, but somewhat less broadly applicable than the advice found in The Art of War. He seems to be very well studied, and likes making lists. I enjoyed this book a lot. In part, I’m sure, because I’m such a fan of Zhuge Liang. Here’s a small sample:

Danger arises in safety, destruction arises in survival. Harm arises in advantage, chaos arises in order. Enlightened people know the obvious when they see the subtle, know the end when they see the beginning; thus there is no way for disaster to happen. This is due to thoughtful consideration.

So that’s my rundown on my studies of the art of war. I will get around to actually reading The Romance of the Three Kingdoms at some point. I also have my eyes on a couple of dramatizations of this story that I might like to watch. If I were going to study this topic any further, I would probably pick up The Art of Peace. I’ll sign off with an old spiritual sung by Nat King Cole:

I’m gonna lay down my sword and shield,

Down by the riverside,

Down by the riverside,

Down by the riverside.

I’m gonna lay down my sword and shield,

Down by the riverside,

Ain’t gonna study war no more.

Ain’t gonna study war no more,

Ain’t gonna study war no more,

Ain’t gonna study war no more.

The I ching often talks in militaristic terms. at times Or at leats political terms of leading and governing to some extent the dao de ching draws upon this leadership lanuage as well.But this warring can be both inner and outter just as governing can be. chapter 62 ''The dao is even a place of escape and support for the bad one'' is a line another brought to my attention yesterday and i think intresting parralles can be found.that being said many thanks for this and all your posts.

Much needed and appreciated, John! 🙏🏽