This is part 2 of a multi-part series.

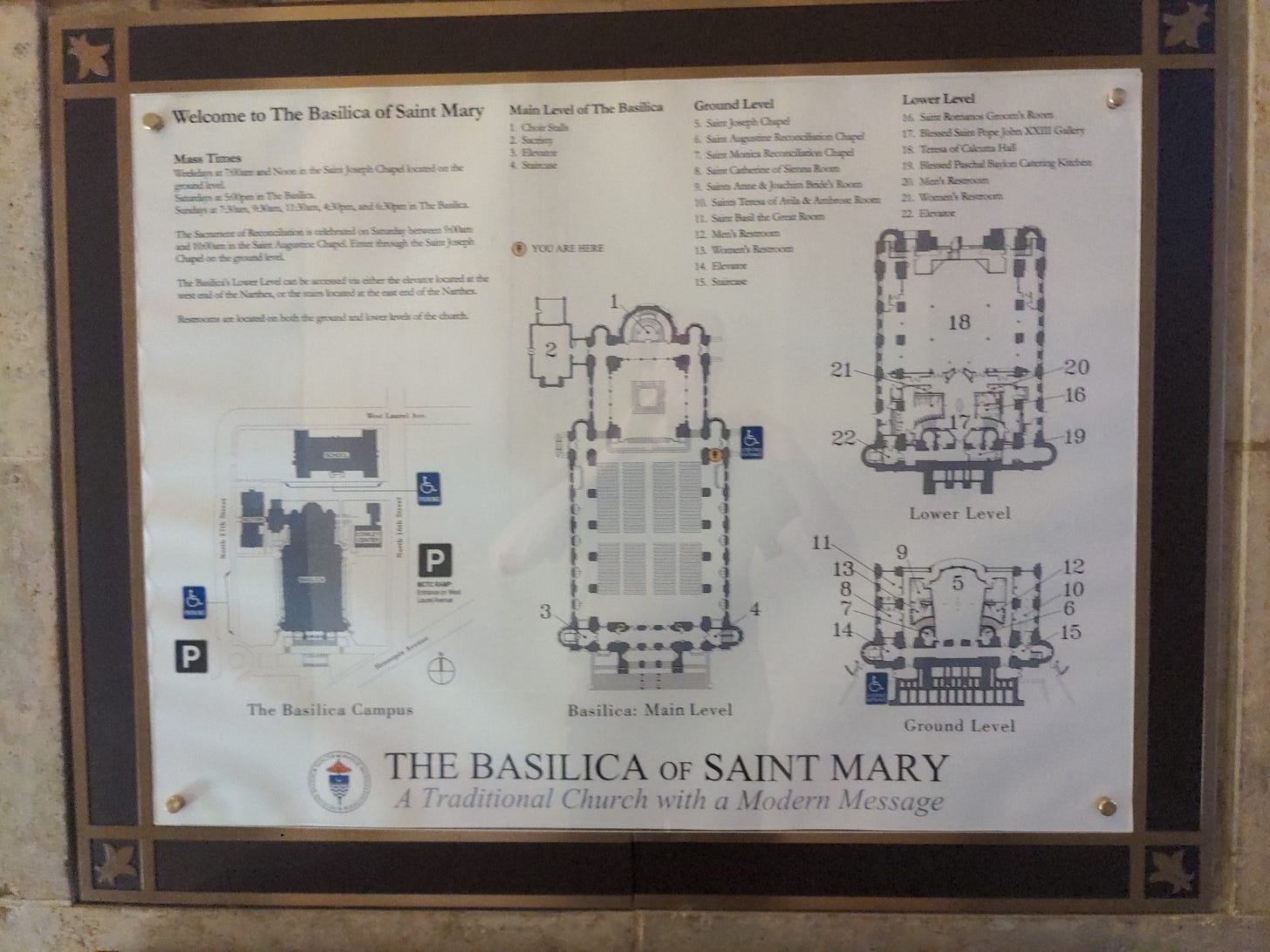

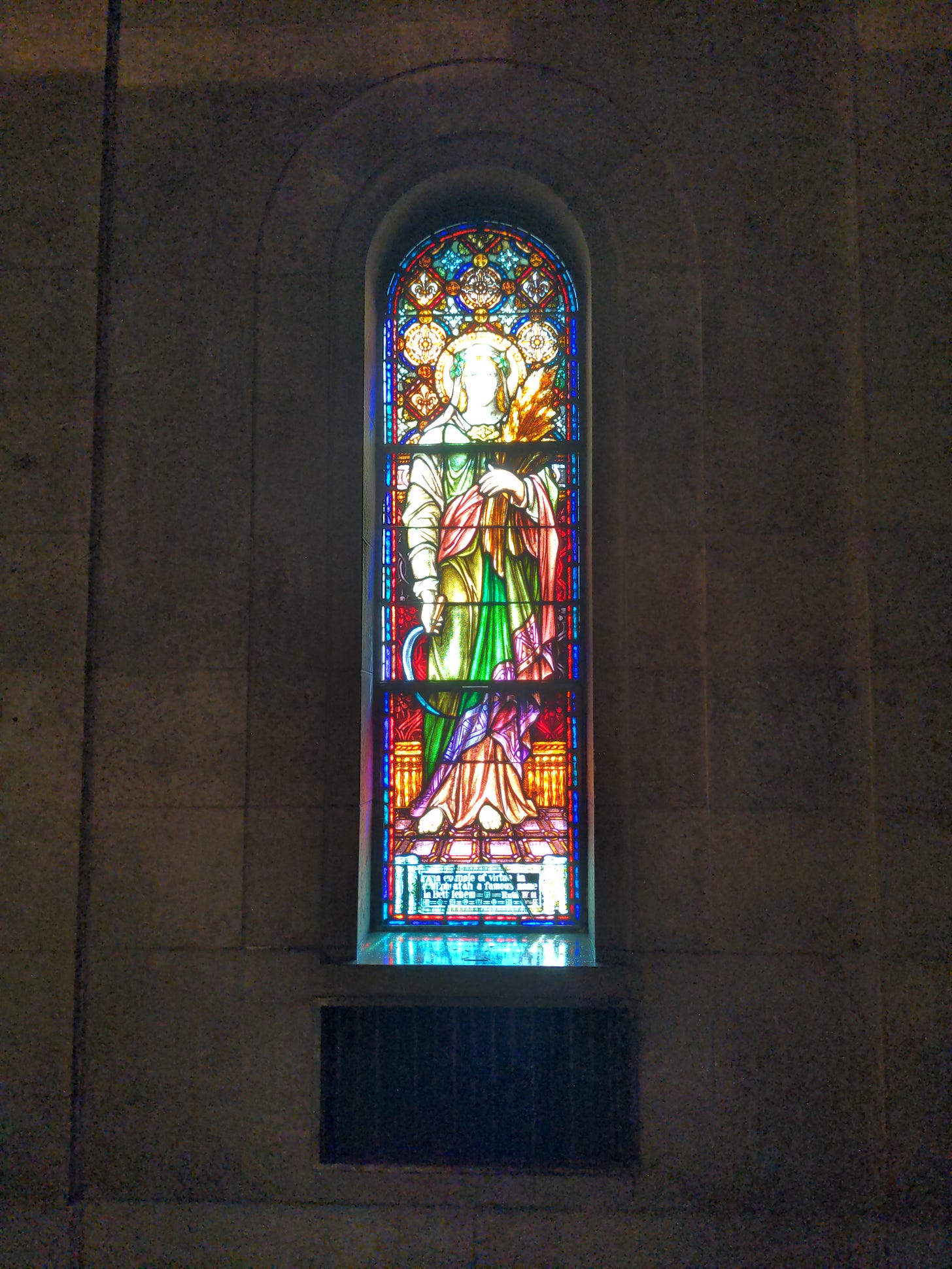

The first stop on my cathedral tour was The Basilica of Saint Mary, which you may well have admired - if you live in the area - through your car window while stuck in traffic on 94, just where it mixes in with Lyndale Ave. I know I’ve done so many times. I originally mistook it for an Orthodox church of some variety, because it has that kind of feel to me:

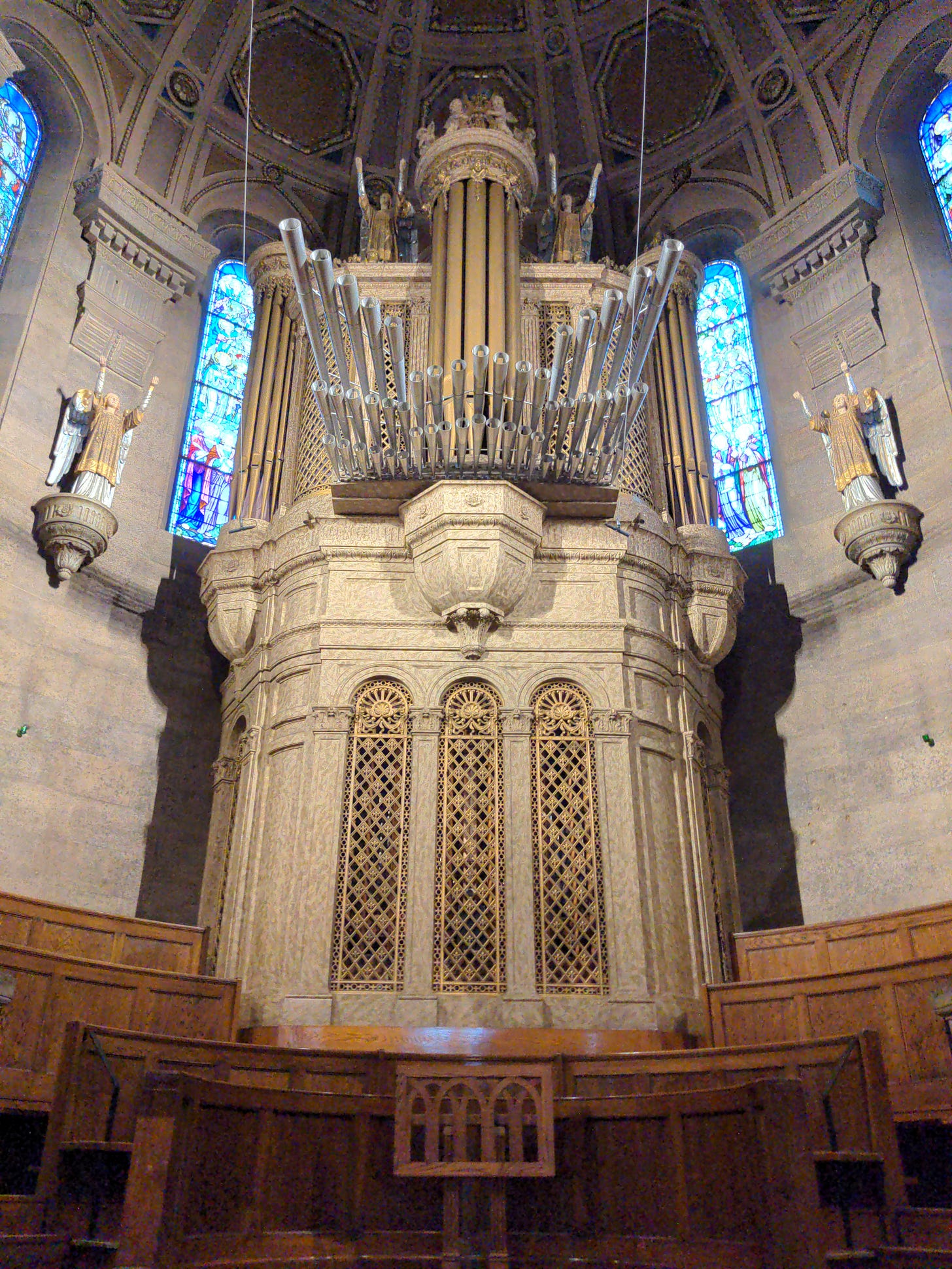

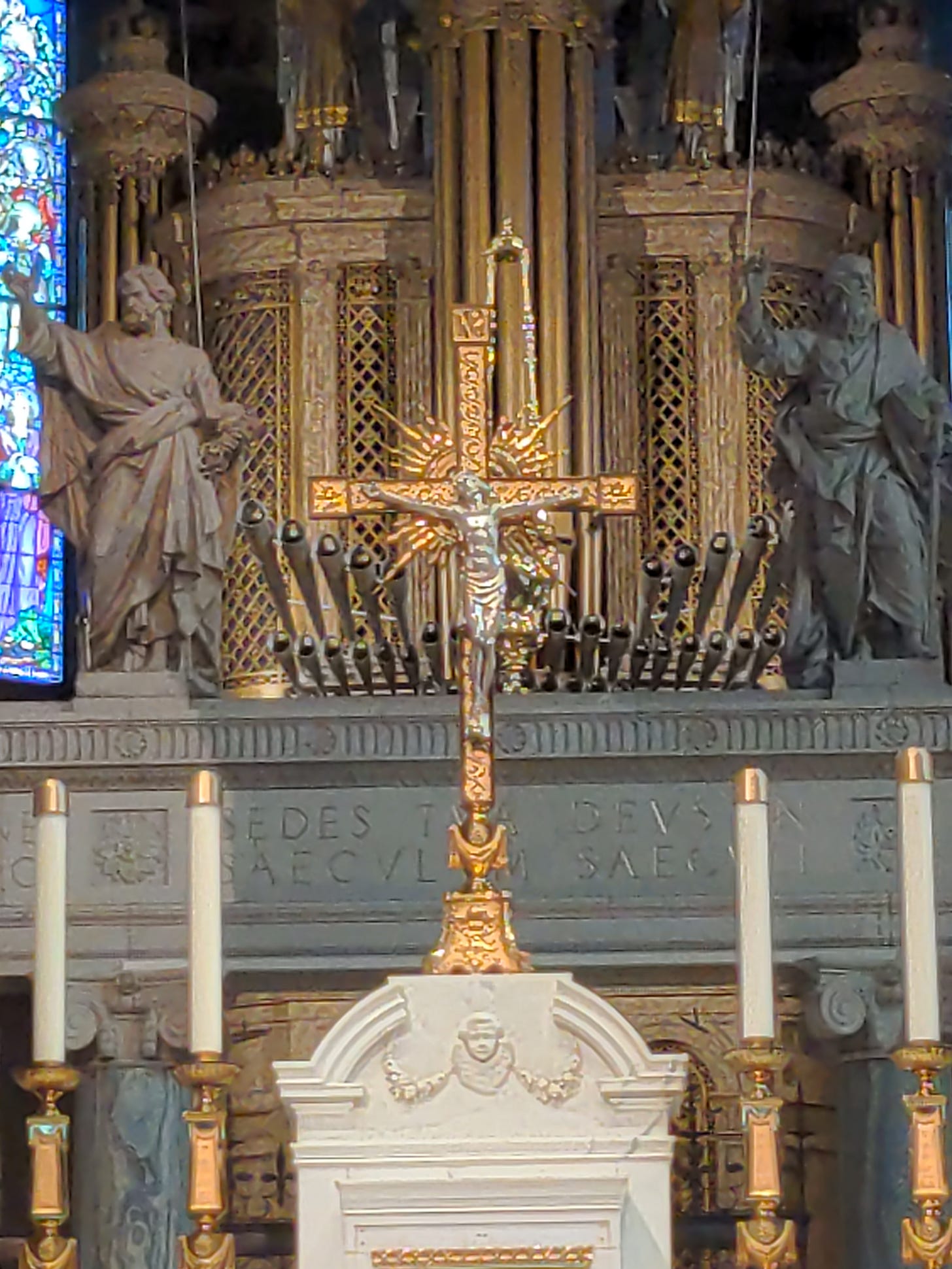

I’ve since found out that it is Catholic. A basilica is like a powered-up cathedral: Whereas a cathedral has a seat for a bishop, a basilica has the seat for the Pope themself. This church was established as a basilica by Pope Pius XI in 1926, making it the first basilica in the United States.

This church is truly gorgeous, inside and out. Like most of the churches I’ve visited so far on this tour, I was greeted and welcomed very warmly. In this case, by a janitor. He let me in the side door and welcomed me to take pictures. And he came back a few minutes later with a pamphlet for a self-guided tour. Unlike the other churches I have been to so far, I must have seen at least a dozen other visitors during the 40 minutes or so that I was there. Other than Saint Mary’s, I haven’t seen anyone in a church yet that wasn’t staff, or at least a member of the congregation.

My general routine is to take a bunch of pictures from the outside, go in and sit in silent prayer for a bit, then go around inside wherever I can taking more pictures. For whatever reason, I’ve taken to sitting in prayer in the center-most seat on the left side, in the third row back. I’m not exactly sure why I do that. It just sort of feels right. And it gives a funny sort of point of comparison between the churches.

I think Saint Mary’s was a great place to start my downtown tour, not because the Catholic church was the first ever church, but because it was the first church that still exists today. I think it’s worth a quick review, in broad-brush terms, of the early years of Christianity, up to the point where we got the Catholic church. It really helps put a bit of perspective on this whole Christianity thing, where it’s taken us, and where it’s heading. Disclaimer: I am not a historian, and while I may well get some of the details wrong, I’m pretty confident that the broad-brush picture I present here is accurate.

After Jesus died in the 30s, there were all different kinds of people going around doing what they felt it meant to be Christian. They traveled from town to town, preaching and proselytizing, and they founded churches in certain towns. They wrote books of sayings that they claimed Jesus to have said, and they wrote letters to each other, and they wrote narratives of the events of Jesus’s life. These people were somewhat diverse, and had different beliefs and practices. Some of them, I am sure, were quite content to let others have their own, opposing beliefs and practices. Some of them couldn’t stand it. Christians naturally formed themselves into groups and, for better or worse, some of them started engaging in in-group / out-group dynamics.

So there was a certain amount of competition for Christian mind-share going on, and at the same time, Christians of all kinds were being persecuted by both the Jews and the Romans. Over time, some Christian groups just dropped off. Perhaps they didn’t have a compelling enough theology and practice to maintain that mind-share. Perhaps they somehow set themselves up for particularly nasty persecution by non-Christian groups. Or perhaps they found themselves persecuted by other, more powerful, Christian groups.

Certainly, all these things happened, and many churches and beliefs that used to be Christian, have fallen by the wayside. Take for example the idea of docetism, which holds that Jesus was fully divine, and that the human form of Jesus was some sort of an illusion. Most Christian churches consider this belief to be heresy, and a docetist of that time would most likely have faced some level of persecution from other Christians. On the other hand, the idea is kind of silly on the surface, probably even to someone living in the second century, so there may well have been challenges getting people to go along with this idea. In any event, it pretty much died off quite early on.

Some of the groups of early Christians that did well included the churches of Peter and Paul. Their beliefs and practices were similar enough that they began to form into a single group, commonly referred to as proto-Orthodox Christians. Sometimes, we see Christian groups break apart over differences of opinions, and at other times, we see groups sometimes compromising and coming together. For instance, one of the major early Christian churches was the Johannite church, which went through a schism (a breaking apart) in its early history. One half of the Johannite church joined up with the proto-Orthodox group, and the other half of the schism didn’t survive. (This story is well-documented in the book The Community of the Beloved Disciple.)

This is the branch of Christianity that would become the official religion of the Roman Empire in the late fourth century AD, and became formalized into the original orthodox Christianity at the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325. The word “orthodox” translates roughly to “correct opinion”, so yeah, these were the people who “got Christianity right”. This is the “catholic” church, which means “universal”. Later on in the history of the church and the Roman Empire, we see other churches coming about, such as the Orthodox churches of the east. But it is important to note that at this point in time, there is only one church, only one correct system of Christian belief, and only one correct Christian practice. Today, some people use the word “catholic” to mean “all those churches and people who got the basic idea right enough to be considered true Christians.” Back then, you were either Catholic, a pagan, or a heretic.

We know very little about most of the early Christian churches that didn’t survive this early portion of Christian history. In fact, in many cases, the most we know, we get second hand from the New Testament, and other surviving texts, telling us that these people were heretics, and not to listen to them. Many of their writings are lost - either destroyed as heresy, or just not having enough mindshare to get copied much. Making copies was pretty costly back then, and only a small number of copies survive.

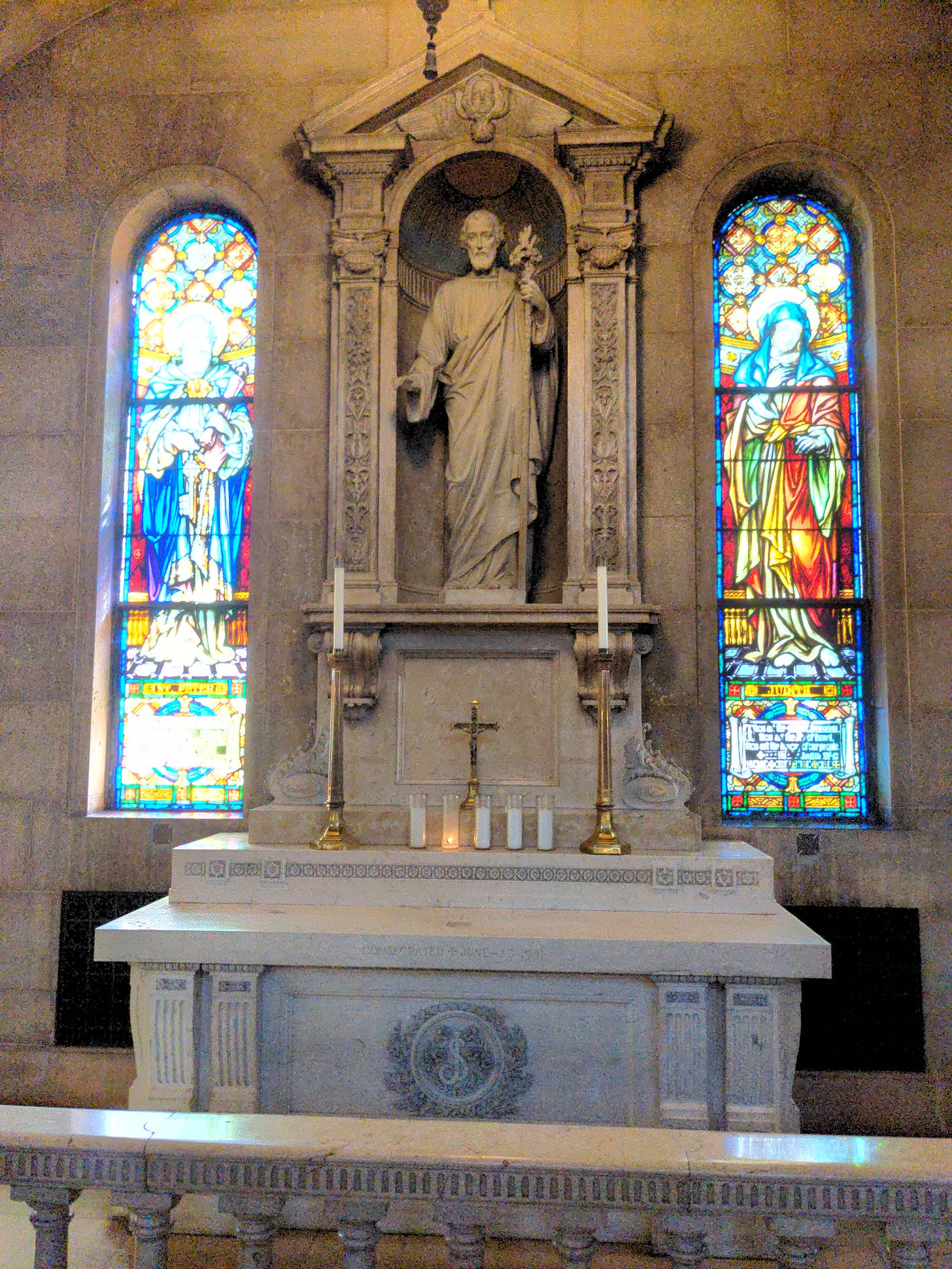

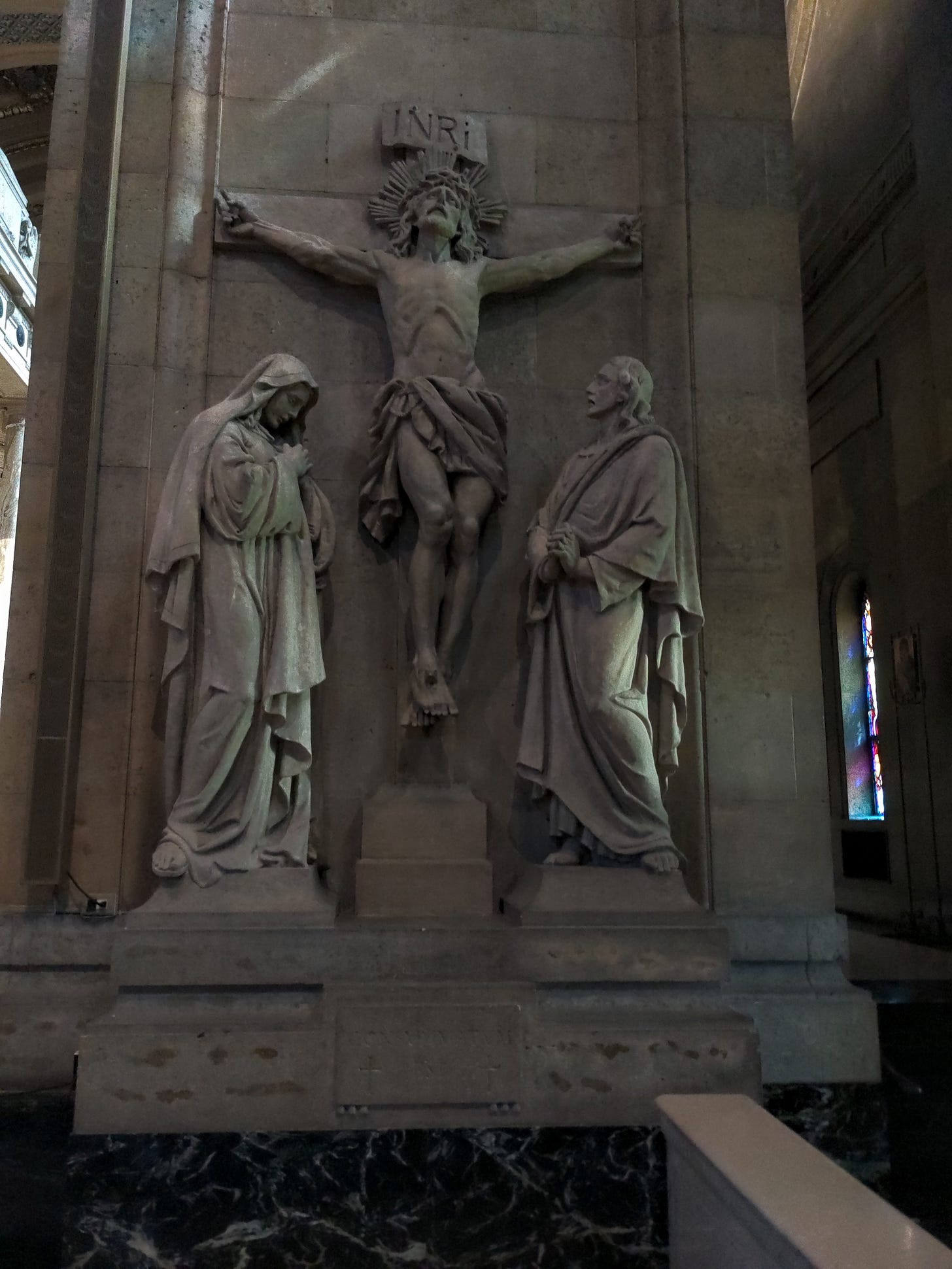

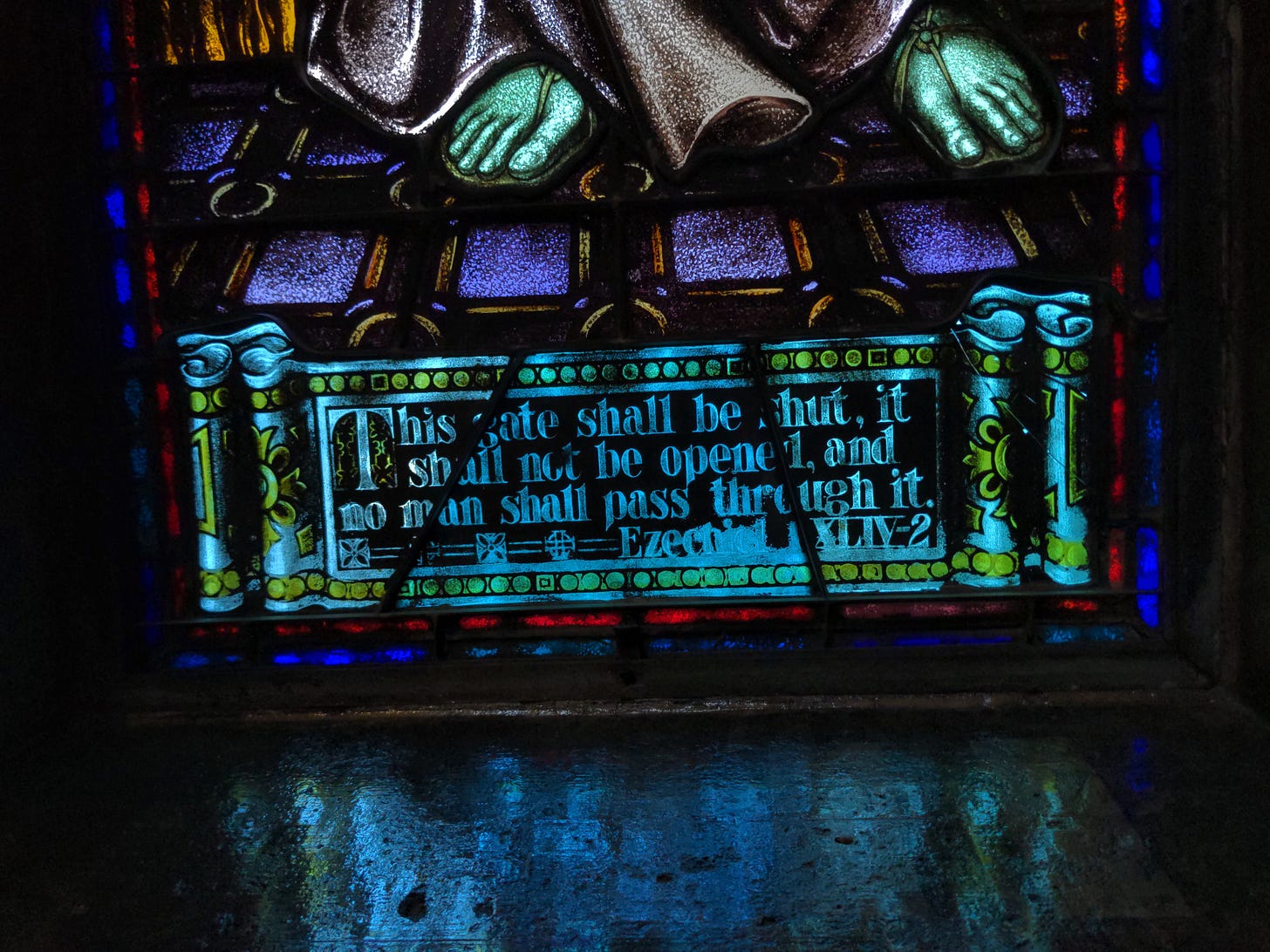

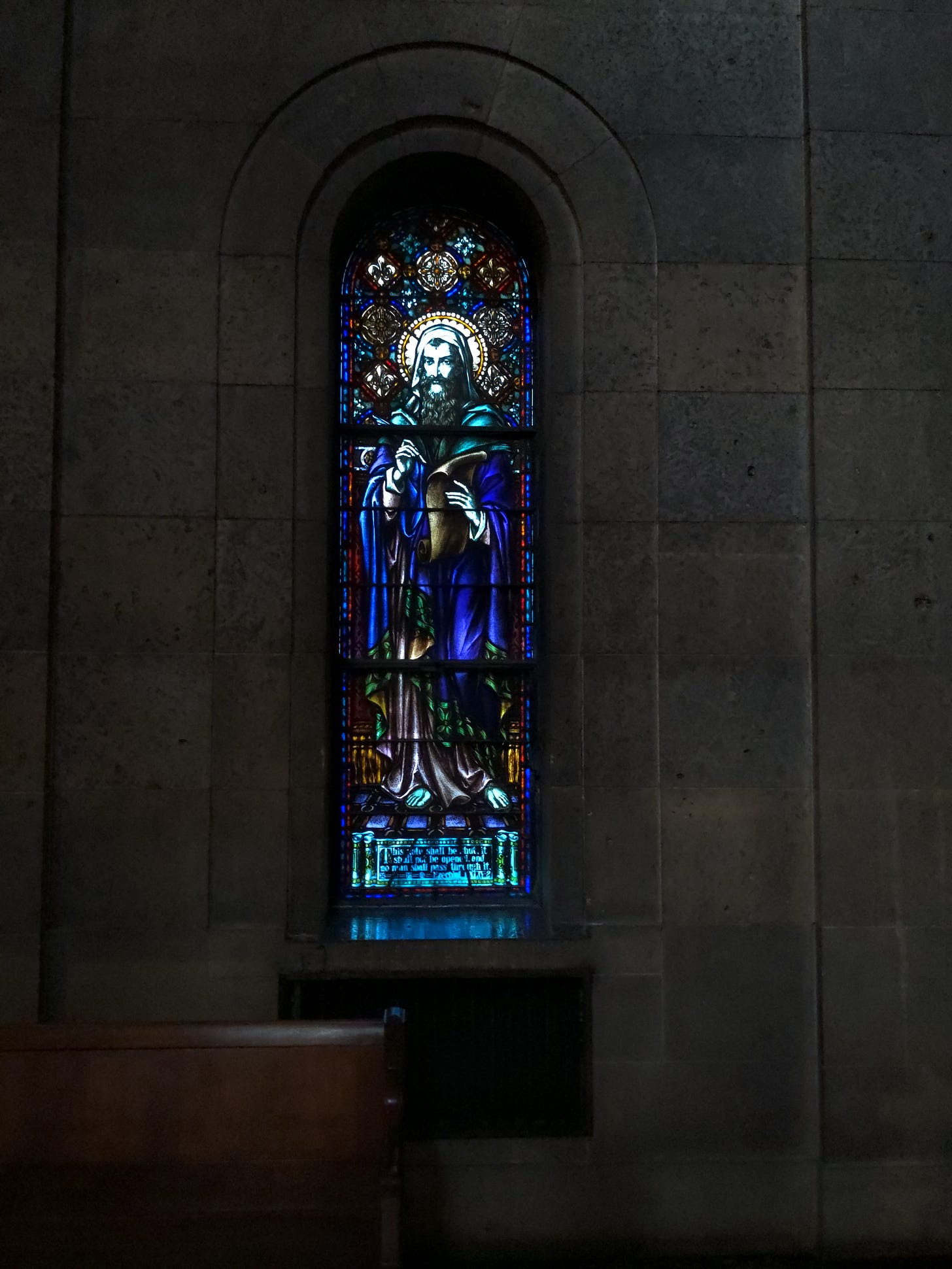

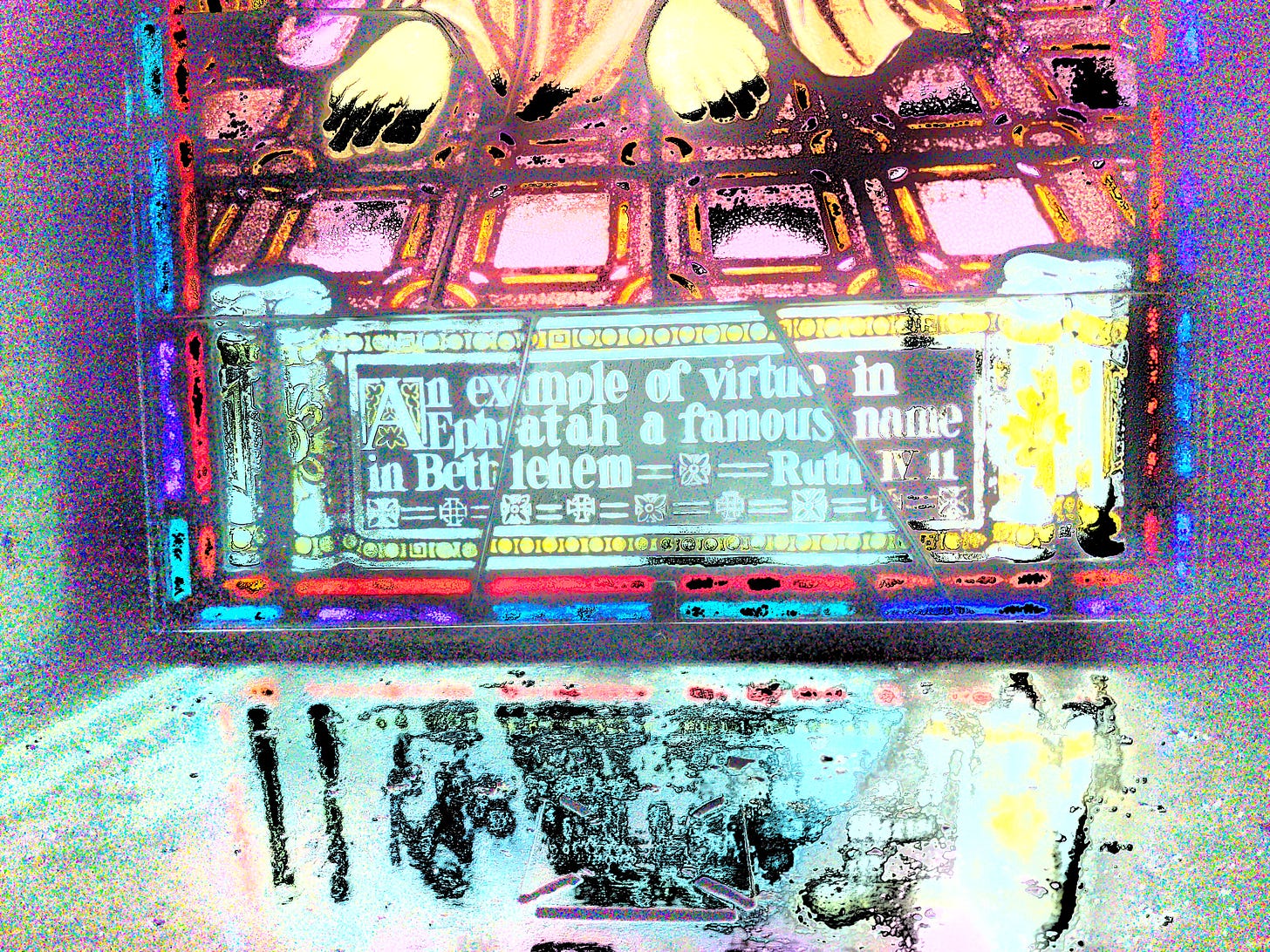

Anyway, enough with the history lesson! On to the pictures! I cannot stress enough that photographs are no substitute with seeing these awesome and beautiful structures in person. But it’s still fun sharing the pics! Here goes, I may throw some commentary in here and there:

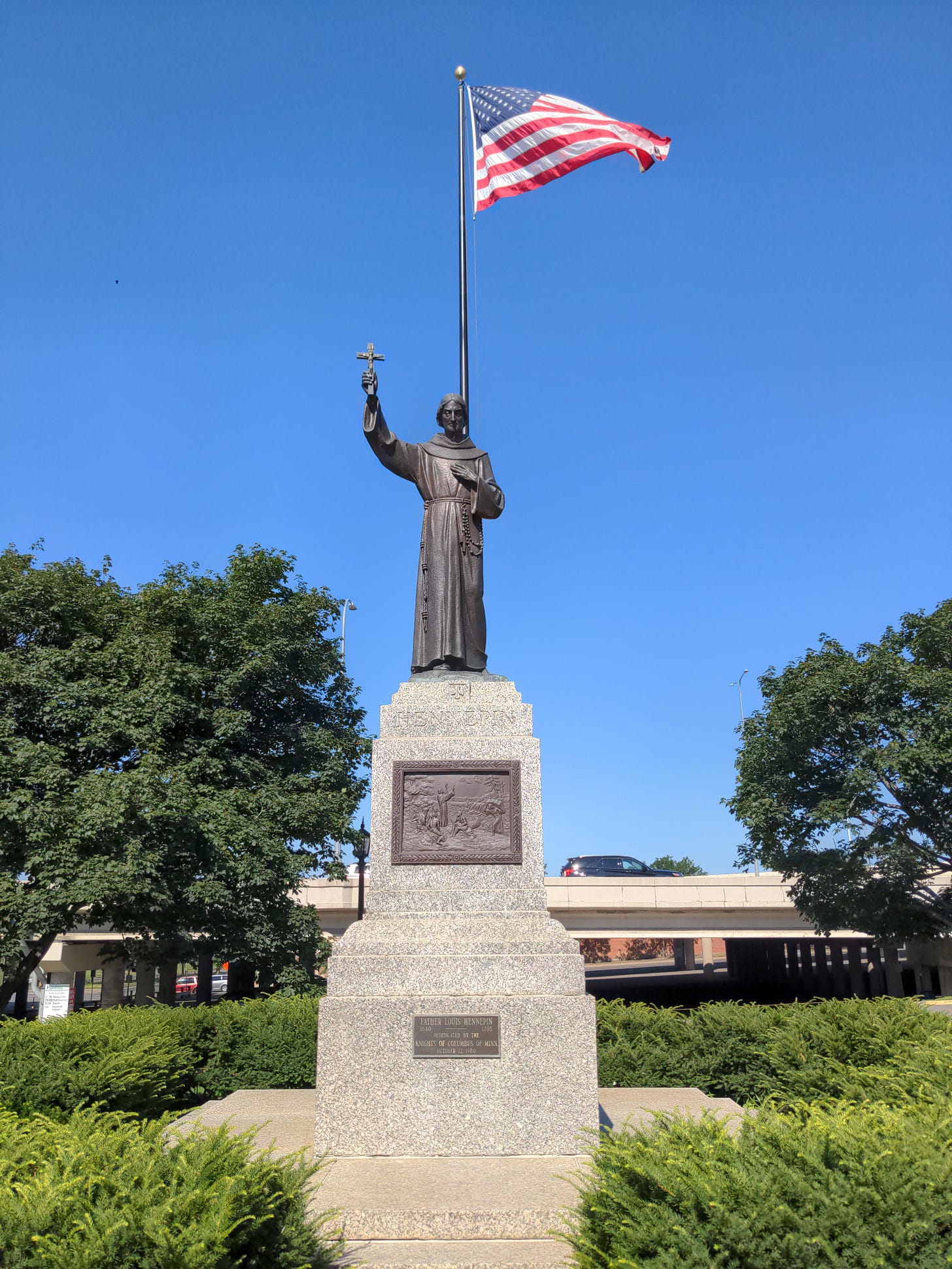

Lots of stuff around Minneapolis is named Hennepin, including a main street in the downtown, and the county that contains it. I learned that these are named after Louis Hennepin, who was a Catholic priest from the 17th century. There’s a statue of him out front:

Part 3 of this blog post series is here:

Exquisite. I also love the story.