This is part three of a multipart series.

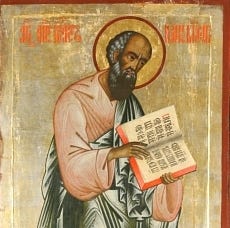

In the previous post in this series, we looked at the three synoptic gospels: Mark, Matthew, and Luke. It only makes sense to look to the Gospel of John next. This gospel presents Jesus with a distinctly high Christology, emphasizing his preexistence, divine nature, and unity with the Father. This contrasts with the Synoptic Gospels, which, while affirming Jesus’s divine identity, develop it more cautiously.

The Gospel of John tells a fascinating and compelling story of the life of Jesus, replete with beautifully poetic theological messaging. Unfortunately, as we will see, it is quite limited in terms of what it can tell us about the historical Jesus. I want to emphasize again that this is no slight on the Gospel of John! It has been, and continues to be, my favorite gospel, not just for its spiritual message, but for its wonderful storytelling. History is not the only source of truth.

As we discussed previously in regards to the Q Gospel, providing an accurate historical account is at odds with promulgating a specific theological message. If the author’s primary goal is to provide an accurate account of Jesus’s life, they will be more inclined to report words and deeds that go against their political views or religious beliefs. Likewise, if the author’s primary goal is to share their vision of God, they will be more inclined to distort, or fail to report, words and deeds that are contrary to their vision. This is important enough to keep in mind that it’s worth an Actual Jesus Heuristic™:

➧AJH #5➧ A theological agenda on the part of the author has a negative correlation with accurate historical accounting.

The theological agenda in the Gospel of John is striking and clear, but the story is not a simple one, as the gospel — as generally accepted by scholarship1 — has gone through three major editions, and the author or authors of each edition had their own agendas. We only have manuscripts for the final edition, and the earlier ones can only be intuited through the techniques of literary analysis. The three editions are:

The Signs Gospel. The earliest version of the Gospel of John is commonly known as the Signs Gospel, or the Signs Source: a narrative that presents seven signs, or miracles performed by Jesus, that testify to his divinity.

The Second Edition with High Christology. This phase is seen as marking a shift from a more narrative-driven account to a more explicitly theological one, emphasizing Jesus' divinity and his preexistence as the Word (Logos).

The Final Redaction. Most scholars agree that the Gospel of John underwent a final stage of editing that aimed to make it more coherent and appealing to a wider Christian audience.2

There is one major passage in John that was added after the Final Redaction: John 7:53–8:11, known as the Pericope Adulterae, where we find Jesus’s famous saying, “Let whosoever among you is without sin be the first to cast a stone at her.”3 This passage is so interesting from a literary criticism point of view that I will discuss it individually in a later essay.

Based on the agendas of the authors of these editions alone, we can expect by AJH #5 that the Signs Gospel to be the most relevant for the study of the historical Jesus. But what about AJH #1? When were these three editions understood to be composed? Scholars generally believe these three editions to be written in these time frames:

The Signs Gospel is thought to have been written 70-90 CE.

Most scholars place the composition of the Second Edition around 90–100 CE.

The Final Redaction is typically dated to 100–110 CE, though some scholars suggest it could extend slightly later.

Given these dates, it is highly unlikely that any of these editions are first-hand accounts. The Signs Gospel, dated slightly later than Mark, most likely developed over time in the Johannine community, largely by oral tradition, until it was eventually formed into a cohesive narrative and written down. There could be some historically accurate accounting in there, but even if it was originally a literal account, there is plenty of room for the story and teachings of Jesus to have been altered in this time frame. By AJH #1 and AJH #5, we can already tell that material from the second and third editions are pretty much useless for helping to understand what Jesus actually said and did.

➧AJH #6➧ Historically accurate accounts in the Gospel of John are only likely to be found in material from the Signs Gospel.

All the manuscripts of the Gospel of John that we have are of the Final Redaction, so we can only piece together the earlier versions by what we can glean from literary analysis. It’s clearly very useful, when reading the gospel, to know which edition the material we are reading originated from. At a high level of granularity, these three editions contribute the following chapters:

John 1-12: The Signs Gospel

John 13-20: The Second Edition

John 21: The Final Redaction

Of course, each new edition is going to make changes to the preexisting text, so just because a verse is from, say, John chapter 3, does not mean the material comes from the Signs Gospel. It is also not true that we have the entire contents of the Signs Gospel in the first 12 chapters of John, as material might have been removed or highly altered in a later edition.

For an example of an addition to existing material, let’s consider the introduction to the book, John 1:1-18. It is clearly in the voice of the Second Edition, and functions as a theological overture that encapsulates the high Christology of the Second Edition authors. It starts:

In the origin there was the Logos, and the Logos was present with God4, and the Logos was God. This one was present with God in the origin. All things came to be through him, and without him came to be not a single thing that has come to be. In him was life, and this life was the light of men. And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not conquer it. There came a man, sent by God, whose name was John; This man came in witness, that he might testify about the light, so that through him all might have faith — But only that he might testify about the light; he was not that light. It was the true light, which illuminates everyone, that was coming into the cosmos. He was in the cosmos, and through him the cosmos came to be, and the cosmos did not recognize him.

Editors can modify earlier material in a number of ways, including:

Adding new material

Removing existing material

Altering existing material

Rearranging existing material

These kinds of changes can happen at different scales, from small matters of wording or phrasing, to the removal or addition of large tracts of text. An example of a smaller addendum occurs in John 1:18:

And turning around, and seeing them following, Jesus says to them, “What do you seek?” And they said to him, “Rabbi” — which is to say, when translated, “Teacher” — “where are you staying?”

Here, the phrase “which is to say, when translated, ‘Teacher’” — more commonly translated into English as “which means teacher” — is added in the Final Redaction. One major purpose of this third edition was to make the text accessible to a wider audience. While the Johannite church was culturally Jewish, Christianity at this time had spread through the Hellenistic world, and the word rabbi may not have been known to them. Furthermore, people somewhat familiar with the word might have understood rabbi to mean a sort of Jewish priest, and the nuance of being a teacher may have been lost. A similar gloss occurs in John 20:16, where the word rabboni — a more elevated form of the word rabbi — appears.

When the outlook and agenda of the authors of two editions are as different as are those of the Signs Gospel and the Second Edition, additional material can be easy enough to spot if we look closely. Once we are aware of the situation with multiple authorship, the more we read the text, the more we are able to get a sense of the differences in the authors’ voices. Similarly, altered text is somewhat easy to spot, as the modified material transforms to be more in the voice of the later author. Furthermore, we can identify the different voices not just by feel, but by more rigorous techniques, such as differences in average word length. We will discuss these processes in more detail in a later essay, where I intend to do a case study in this kind of analysis. The larger the addition or alteration is, the easier it is to spot, because we have more material to work with to look for clues.

Removals and rearrangements can be harder to spot than additions or alterations, because of the lack of presence of the new voice. Generally speaking, all removals can be considered lost, because it is impossible to reconstruct missing passages excepting with the most tenuous confidence. However, all four sorts of redactions we are discussing can often be identified by what scholars call seems, or points in a text where different sources, edits, or redactions meet, often marked by abrupt shifts in style, content, or narrative flow.

One obvious example of a seem in the Gospel of John is the transition from chapter 20 to chapter 21. The final two verses of John 20 are clearly intended as a conclusion to the gospel:

Of course, Jesus performed many other signs as well before the disciples, which have not been recorded in this book; But these ones have been recorded so that you might have faith that Jesus is the Anointed, the Son of God, and that in having faith you might have life in his name.

John 21 then begins by abruptly transitioning into another post-resurrection story:

Thereafter Jesus again manifested himself to the disciples of the Sea of Tiberias; and this was the manner in which he manifested himself:

Of course, we do not need to go into deep research in order to identify seems, or figure out which edition of the Gospel of John any particular passage originates from. This work has already been thoroughly and credibly done by biblical scholars. These scholars write academic papers on the topic, as well as long, deeply fascinating books that most of us do not have time to read. But online resources are available to summarize their findings.

Personally, when I wish to dig in to a certain passage or verse, I find AI to be a useful tool. At this time, you have to be careful with AIs, because they tend to be overly agreeable, and often share false — or even entirely made-up — information. I’m always careful to double-check its responses by asking followup questions, and using other online resources. You should always be able to get a clear idea of which edition any passage originated from with a minimal amount of research using these tools.

In case you are interested in learning about the Gospel of John in more detail, here are a handful of books that I have not had time to read yet, but look promising:

Raymond E. Brown – The Gospel According to John (Anchor Yale Bible, Volumes 1 & 2)

A foundational, in-depth commentary that discusses source layers, redactional history, and theological development. Brown outlines the theory of the Signs Gospel and later theological expansions.

Rudolf Bultmann – The Gospel of John: A Commentary

A classic form-critical analysis that identifies various sources and redactional layers in John.

J. Louis Martyn – History and Theology in the Fourth Gospel

Focuses on the Johannine Community and how different stages of composition reflect historical conflicts (e.g., tensions with Jewish authorities).

D. Moody Smith – John Among the Gospels

Explores how John’s composition evolved, comparing it with Synoptic traditions and internal redactional evidence.

While I am relying on scholarship here quite a bit, I don’t do it blindly. I have reason to believe that the current scholarship on the Gospel of John is largely reliable. I have more doubt when it comes to the Gospel of Thomas. When I get around to discussing that text, remind me to bring it up.

The story of how the Johannine community merged with the proto-Orthodox church of Peter, Paul and James is a fascinating one, but it’s not terribly relevant to our present purposes. If you are interested, I can highly recommend a short book called The Community of the Beloved Disciple, by Raymond Brown, which I review here.

As usual, I quote from the New Testament translation of David Bentley Hart.

Hart has a somewhat complicated manner, by using various combinations of uppercase and lowercase, of differentiating between the different uses of the word "theos" (θεός) in the prologue to the Gospel of John. He spends about four pages in the postscript describing his system and the reasoning behind it. As it might have been a bit jarring and confusing in a brief excerpt here, I thought it best to simply use “God” throughout in this passage. I mean no disrespect to the translator by this.